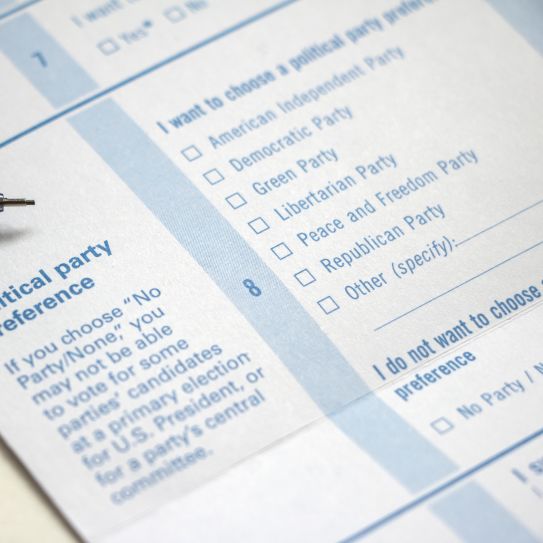

What You Buy Could Reveal How You Vote

The social media we follow and what we consume says a lot about our political affiliations.

Popping into Starbucks for a latte or ordering a sandwich at Chick-fil-A could reveal something about your political opinions.

According to research by Oded Netzer, the Arthur J. Samberg Professor of Business, the ever-widening gap between identities in the United States goes beyond the political beliefs of conservatives and liberals. It stretches to the products we consume, the entertainment we watch, the places we eat, or the sports team we root for.

“We know that we’ve become more politically polarized as a country since the 2016 election,” Netzer says. “But our research shows that we are also more polarized in what we buy and the way we associate ourselves with these products.”

Netzer and co-authors Verena Schoenmueller of Bocconi University and Florian Stahl of the University of Mannheim used publicly available data from more than 150 million Twitter accounts to track the political affiliation of users based on the political accounts they follow.

“Many social media users publicly ‘announce’ their political preferences through the political accounts they follow,” says Netzer. The researchers also tracked which partisan accounts are followed by more than 600 commercial brand profiles.

So, does the partisan divide between Democrats and Republicans extend to the products they buy?

The answer, to a large extent, is yes.

“The differences are deep and they are wide,” Netzer says. “It is evident in the beer they drink, the celebrities they follow, and the sports they watch. What liberals and conservatives consume is different in meaningful ways.”

The researchers created a publicly available website that allows users to evaluate the political affiliation of a brand based on the political preferences of its Twitter followers.

In the case of Starbucks, 68 percent of their followers supported Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, while 58 percent of Chick-fil-A followers backed Donald Trump.

In their paper, Netzer and his colleagues look beyond a snapshot view of brand political affiliation, examining both how companies’ politics changed after the 2016 election and what motivates people to patronize organizations that represent their politics.

They demonstrated that consumer choices became more polarized following the election, especially among liberals. When their political identities were “threatened,” after Trump won, liberals started to engage in what the researchers call compensatory consumption — spending money in such a way that makes up for a perceived deficit or slight.

“In 2016, because of the surprise election results, liberals felt their identities were threatened,” Netzer says. “They took action that symbolizes their identities, such as buying clothes and following brands that tilt leftward, and hence would reflect their beliefs.”

Netzer notes that a person’s decision to support or follow a brand that symbolizes their political beliefs may be subtle or even subconscious.

Netzer found that in the aftermath of Trump’s election, products by companies that are more left-leaning saw an increase in support from liberals, but products that signify a rightward bent did not see such an increase in support from conservatives, since their identities were not subject to the same level of threat.

But if on November 3 Democratic nominee Joe Biden wins the presidency, Netzer thinks that there could be a role reversal, and those who identify with the GOP would now consider themselves threatened, and thus increase their support for products that symbolize their politics.

Netzer says brands do not need to take significant political action to be recognized as partisan, since consumers often have a sense of who else is likely buying it. For example, Starbucks has not made any overtly partisan statements, but consumers may inherently know that most of its customer base is liberal.

But as has been evident in recent years, companies do involve themselves in political debate.

“Since the 2016 presidential election, we have seen a significant increase in brands taking political stands,” Netzer says. “These brands, indeed, were able to attract consumers who are in line with the stand they took.”

About the Researcher

More Features

Value Investing: How CBS is Staying Ahead of the Curve

Learn how Columbia Business School is updating its acclaimed value investing curriculum to align with a rapidly changing financial landscape.

The Fed and Interest Rates: Is Flexibility the Best Approach?

Professor Pierre Yared talks about his recent research, which looks at the rising popularity of guiding monetary policy through target-based rules.

Interest Rates and Inflation: What’s Next for the Federal Reserve?

Professor Pierre Yared describes why the U.S. economy is unlikely to see an economic downturn comparable with the 1970s.

Can We Curb Fake News? Smart Research May Provide the Answer

Professor Gita Johar shares research insights on why it spreads, spotting who shares it, and a multi-pronged approach to reduce it.

Rise to the challenge.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world of business, while bringing historical inequities and injustice into sharp relief.

Subscribe to Leading Through Change to receive the latest insights from Columbia Business School to help you navigate this unprecedented time.